200 hrs Yoga TTC

Module 4

Professional Essentials - (50 hours)

Teaching methodology (sequencing, cueing, pacing, class management) – 25 hrs

CUEING

Cueing is the art of giving clear, concise, and effective verbal and non-verbal instructions to guide students safely and meaningfully through a yoga practice.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this module, trainees should be able to:

Deliver clear, easy-to-follow instructions.

Use cues that support alignment, safety, and awareness.

Adapt cues for different levels and learning styles.

Communicate with confidence and presence.

Types of Cues

TypePurposeExample:

Action Cues - Tell students what to do“Press your feet firmly into the mat.”

Alignment - Expalin how to position the body“Knee stacked directly above the ankle.”

Anatomical Cues -Reference body parts to refine awareness“Engage your quadriceps to lift the kneecaps.”

Directional Cues - Indicate spatial orientation“Reach your arms up toward the ceiling.”

Energetic / Qualitative Cues - Invite subtle awareness“Feel your spine lengthen with each inhale.”

Breath Cues - Sync movement with breath“Inhale to lift, exhale to fold.”

Safety Cues -Prevent injury“Avoid locking your elbows; keep a soft bend.”

Inspirational / Mindful Cues - Deepen focus and intention“Find steadiness even in the wobble.”

Cueing Guidelines

Keep it simple: Use short, active sentences. (“Step your right foot forward” instead of “If you’d like, you can bring your right foot forward now.”)

Cue one action per breath.

Speak before movement: Give the cue, then allow time to respond.

Use positive language: “Keep your shoulders relaxed” rather than “Don’t tense your shoulders.”

Layer your cues: Start with safety → alignment → refinement → energetic awareness.

Model awareness: Use tone and pace of voice that matches the energy of the class.

Avoid over-cueing: Give space for students to experience the pose.

Practice Exercise

Teach Tadasana using only action and alignment cues.

Repeat using breath and energetic cues.

Reflect: Which felt clearer? Which invited more presence?

PACING

Pacing refers to the rhythm and timing of your class — how quickly or slowly you guide students through movements, holds, and transitions.

Learning Objectives

Trainees will learn to:

Maintain a steady, mindful rhythm appropriate to class style and level.

Balance stillness and flow to match energetic intention.

Adapt pacing to breath, music, and group energy.

Components of Pacing

ElementDescription:

Breath Rhythm -Match verbal cues and transitions to the student’s natural breath cycle.

Pose Duration - Time spent holding poses affects intensity and focus.

Transition Flow - Smooth linking between poses maintains meditative continuity.

Voice Pace -Speed, tone, and pauses affect student experience.

Energy Arc - Class builds gradually, peaks, and resolves (opening → warming → peak → cooling → rest).

Pacing Guidelines

Teach with breath: One movement per breath in vinyasa; longer holds in hatha or yin.

Start slow: Allow students to settle before increasing tempo.

Notice your voice: Match tone to class energy (calm in yin, vibrant in flow).

Allow silence: Don’t fill every moment — pauses let students internalize cues.

Use music intentionally: Let rhythm support, not dominate.

Observe students: Adjust speed if the class looks rushed or disengaged.

Stay aware of time: Know your sequence and allocate minutes per section.

Practice Exercise

Lead a 10-minute mini-class.

Record yourself and check for pacing: Are there pauses, breath synchronization, and energetic build-up?

TEACHER PREPARATION & GROUNDING TOOLS

Arriving Calm, Centred, and Ready to Teach

Teaching yoga is an act of service — it begins not when you cue the first pose, but when you arrive in the space.

A teacher’s energy sets the tone for the class. Taking even a few mindful minutes before students arrive can transform nervousness into calm, and self-doubt into presence.

Before Class: Arrive and Ground

1. Arrive Early

Aim to arrive 15–20 minutes before class.

Use this time to settle into the environment, set up props, check lighting, music, and temperature.

Avoid rushing — give yourself the same grace and spaciousness you offer your students.

Grounding and Centering Tools

1. Conscious Breathing (Pranayama for Calm)

Sit quietly and take 5 slow, deep breaths in and out through the nose.

Try Box Breathing (Sama Vritti): Inhale 4 – Hold 4 – Exhale 4 – Hold 4.

Or Lengthened Exhale Breathing: Inhale for 4, exhale for 6–8.

Purpose: Regulates the nervous system and brings focus inward.

2. Body Awareness Scan

Sit or stand, close your eyes, and gently notice your body.

Bring awareness from the soles of your feet up to the crown of your head.

Release tension in your shoulders, jaw, and belly - Purpose: Brings you back into your body — the most grounded place to teach from.

3. Rooting Visualization

Feel the points of contact with the ground — your feet, your seat.

Imagine roots extending deep into the earth, anchoring you in stability and ease.

On each exhale, release any tension or anxiety through those roots. - Purpose: Creates energetic grounding and emotional steadiness.

4. Centering Mantra or Affirmation

Silently repeat a phrase that connects you to your purpose, such as:

“I am calm, grounded, and ready to share.”

“I offer this class with love and presence.”

“May I be of service.” - Purpose: Aligns the mind and heart with intention rather than fear.

5. Simple Movement

Gentle stretches, shoulder rolls, cat-cow, or a few rounds of Surya Namaskar A.

Move with breath to release nervous energy. - Purpose: Clears tension and awakens vitality before teaching.

6. Silent Sitting or Meditation

Take 2–5 minutes of stillness before students arrive.

Simply sit, breathe, and sense the energy of the space.

Allow thoughts to settle naturally. - Purpose: Invites mental clarity and presence.

7. Energetic Cleansing (Optional)

If the space feels heavy or busy, take a few deep breaths and imagine exhaling light into the room.

You can use subtle rituals (like lighting incense or ringing a bell) if appropriate to the setting.- Purpose: Helps reset the energy of the space with awareness and intention.

Practical Tips for Calm & Confidence

Know your sequence: Have a clear plan and backup options.

Simplify your goals: Focus on one main intention or theme for the class.

Let go of perfection: Teaching is a practice — stay open, present, and kind to yourself.

Trust your preparation: Once class begins, shift from thinking to feeling.

Smile and breathe: A genuine smile relaxes both teacher and students.

Reflection Prompt for Trainees

“What practices help me feel most grounded before teaching? How can I make those a consistent part of my teaching ritual?”

CLASS MANAGEMENT

Class management is the skill of creating a safe, inclusive, and focused environment where students can practice with confidence and comfort.

Learning Objectives

Trainees will learn to:

Manage group dynamics and space effectively.

Offer modifications and props.

Maintain safety and inclusivity.

Handle disruptions or challenges calmly and professionally.

Key Aspects

Area Guidelines

Environment Setup -Check temperature, lighting, floor space, mat placement, props accessible.

Class Intention - Begin with centering and clear purpose (theme, focus, or intention).

Demonstrations -Keep short and purposeful; move around to observe students.

Observations & Adjustments -Offer verbal or hands-on adjustments (with consent).

Energy Awareness - Read the room; adapt your plan if needed (slower, quieter, or more dynamic).

Time Management - Begin and end punctually; plan for transitions.

Inclusivity - Use neutral language, offer options for all bodies and abilities

.Professional Presence -Stay calm, kind, and confident. Avoid overexplaining or apologizing.

Practice Exercise

Teach a 15-minute class managing space, props, and student feedback.

Peer review using these questions:

Was the environment organized?

Did the teacher maintain flow and attention?

Were instructions inclusive and safe?

Integration Assignment (for Trainees)

Write a 1-page reflection on how cueing, pacing, and class management influence the energetic experience of a yoga class.

Record a 10-minute teaching demo integrating all three elements.

Receive peer and mentor feedback.

PRACTICAL CASE STUDIES & GROUP WORKSHOPS

Refer back to Module 1 - Sequencing, safety and adaptations and look at the sample templates for planning your home case studies below.

Home case studies - choose 3 case studies and video the class of 60 minutes based on the baove template and email directly to me for feedback.

Design a 60-min Class for Mixed Abilities

Choose a theme (e.g., grounding, heart-opening, stability).

Sequence: 3 warm-ups, 4 main standing poses, 2 floor poses, 2 restorative.

Include one contraindicated student scenario and how you would adapt it.

Pose Breakdown Practice

Work in pairs: one teacher cues, one practices.

Observe and correct alignment using tactile and verbal cues.

Identify key muscles and joints active/inhibited (Ray Long anatomy emphasis).

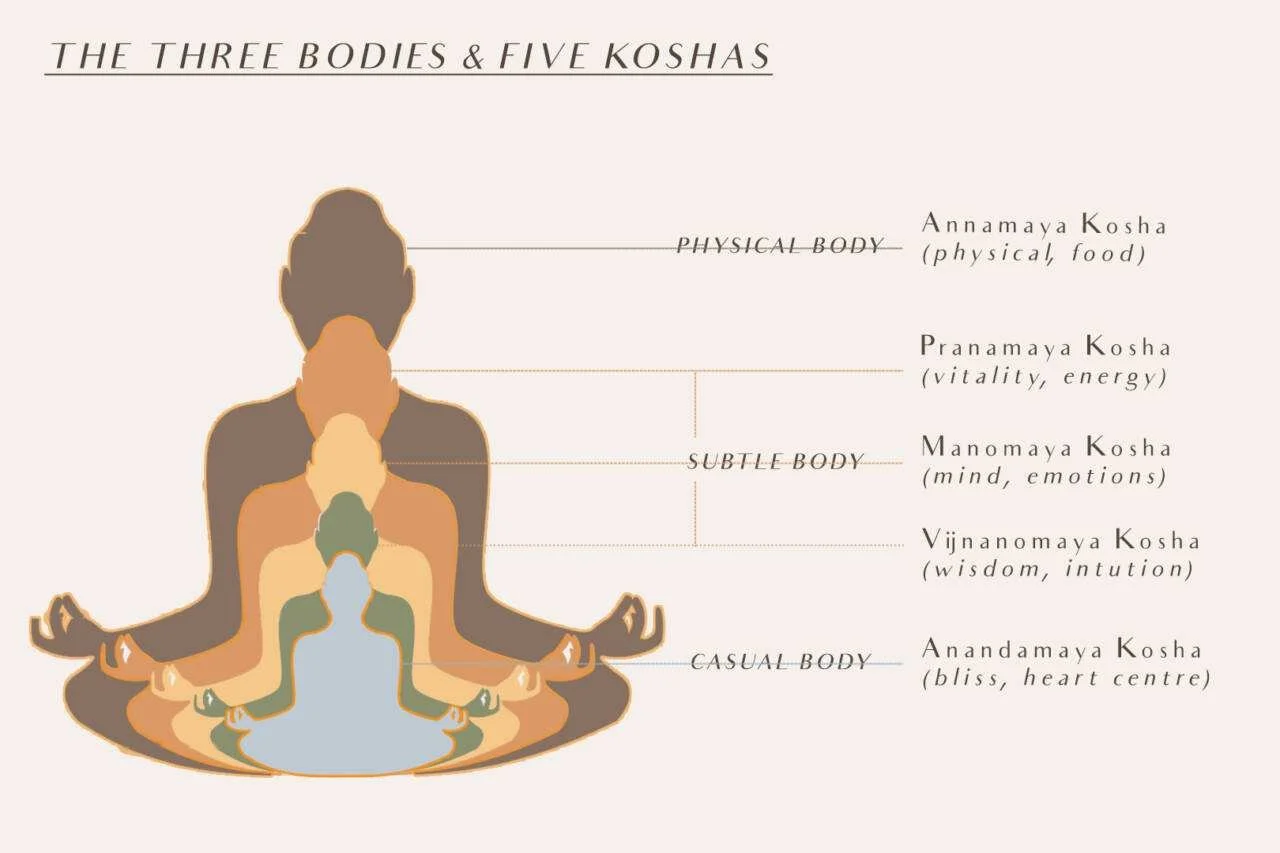

The Three Bodies (Shariras) & Koshas

1. The Physical Body — Sthula Sharira

The physical body is our outermost expression, made of the five elements—earth, water, fire, air, and ether. It includes flesh, bone, tissues, and all that can be seen and touched. It is the vessel through which we experience the world.

This body corresponds to the Annamaya Kosha, the sheath made of food.

2. The Subtle (Astral) Body — Sukshma Sharira

The subtle body vibrates at a higher frequency than the physical form. It contains the prana (life force), manas (mind), buddhi (intellect), and ahamkara (ego). Within it flow the 72,000 nadis (energy channels), the chakras, and the pranavayus (vital currents).

This body corresponds to three koshas—Pranamaya, Manomaya, and Vijnanamaya.

3. The Causal Body — Karana Sharira

The causal body is the most subtle, the seed of individuality. It is beyond intellect and mind—pure potentiality, the storehouse of karmic impressions. Within it resides the Anandamaya Kosha, the sheath of bliss.

It is here that consciousness rests in stillness, untouched by time or change.

The Five Koshas (Pancha Kosha)

Described in the Taittiriya Upanishad, the five koshas represent successive layers of experience that veil the Self (Atman). Through yoga, meditation, and self-inquiry, we journey inward—peeling back these layers to realize the truth of who we are.

1. Annamaya Kosha — The Physical Sheath (Food Body)

The word Anna means “food.” This sheath represents the tangible, physical form—bones, muscles, and organs. It sustains and nourishes the other koshas and connects us to the earth element.

Practices to Balance Annamaya:

Conscious eating and proper nourishment

Asana (yoga postures) for flexibility and grounding

Adequate rest, movement, and alignment with natural rhythms

Practice Reflection:

As you move through asana or mindful walking, feel the strength and steadiness of your body.

Can you experience it as sacred earth—temporary yet radiant with life?

2. Pranamaya Kosha — The Vital Energy Sheath

Prana means “life force” or “that which breathes.” This sheath governs all vital functions—breathing, circulation, digestion, and cellular vitality. It links the body and the mind.

The Pranamaya Kosha corresponds to the water element—fluid, adaptable, and purifying.

Within this sheath flow the pranavayus, nadis, and chakras that distribute energy throughout the system.

Practices to Balance Pranamaya:

Pranayama (breath control)

Awareness of energy flow in asana

Balancing activity and stillness

Practice Reflection:

Take a few conscious breaths. Feel how prana moves through your body.

What does it feel like to be breathed—rather than the one who breathes?

3. Manomaya Kosha — The Mental Sheath

Manas means “mind.” This kosha includes our thoughts, emotions, desires, and sensory experiences. It governs perception and response, shaping how we interpret the world.

It corresponds to the fire element, representing transformation and clarity.

Practices to Balance Manomaya:

Mantra repetition (Japa) to steady thought currents

Mindfulness of emotions without judgment

Dharana (concentration) and meditative awareness

Practice Reflection:

Observe your thoughts as ripples on the surface of a lake.

Who is the one observing? How does awareness remain still beneath the movement?

4. Vijnanamaya Kosha — The Wisdom Sheath

Vijnana means “knowing” or “discernment.” This sheath represents intuition, higher understanding, and the faculty of discrimination between the real and the unreal.

It is associated with the air element, light and expansive.

When this kosha is balanced, actions flow from clarity and compassion. The ego softens, and choices align with dharma—our higher purpose.

Practices to Balance Vijnanamaya:

Self-inquiry (Atma Vichara)

Study of sacred texts and reflective journaling

Awareness of moral and intuitive guidance

Practice Reflection:

Bring awareness to a recent choice or challenge.

How might wisdom arise when you listen not from the mind, but from the still space of inner knowing?

5. Anandamaya Kosha — The Bliss Sheath

Ananda means “bliss.” This innermost sheath is not emotional pleasure but the deep peace that arises when mind and senses are quiet. It is the radiance of the soul itself—the unchanging joy of pure being.

It resonates with the ether element, vast and boundless.

This sheath is experienced in deep meditation or stillness when identification with form dissolves. It is the silent witness, the essence of all existence.

Practices to Touch Anandamaya:

Meditation and mantra

Surrender (Ishvara Pranidhana)

Resting in silence after practice

Practice Reflection:

Sit quietly and notice the subtle hum of stillness within.

What remains when thought subsides? Can you feel peace that needs no reason?

Integrating the Koshas

The five koshas are not separate layers but interwoven expressions of consciousness.

They correspond to our states of awareness:

Waking (Jagrat): Annamaya and Pranamaya

Dreaming (Svapna): Manomaya

Deep Sleep (Sushupti): Vijnanamaya and Anandamaya

Through yoga, pranayama, meditation, and self-inquiry, we journey from the outermost sheath toward the innermost. As the veils of Māyā dissolve, the truth of Atman—the eternal Self—shines forth.

“The goal of life is to realize your inner Self, the Self of all beings.

Peel off the sheaths, layer by layer, and rest in that pure consciousness.”

— Swami Sivananda

Closing Reflection

Take a few moments of stillness.

Sense your body, your breath, your mind.

Recognize that each is a doorway inward.

As you move through your practice and your days, remember:

You are not the body, nor the breath, nor the mind—

You are the light that illumines them all.

“Through the knowledge of the five sheaths, one attains the knowledge of the Self.”

— Taittiriya Upanishad

Chakras

In Transformational Yoga, chakras are not merely energy centers in the subtle body, they are levels of consciousness, each corresponding to a specific domain of human experience. The practice works to purify, activate, and harmonise the chakras so that energy (prana) flows freely, allowing transformation of the physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual layers.

There are seven primary chakras recognised in this system, each connected to an element, a function, and a beej mantra.The primordial vibration that activates and balances its energy.

🔺 1. Muladhara Chakra – Root Chakra

Location: Base of the spine

Element: Earth

Quality: Stability, survival, grounding, physical vitality

Beej Mantra: LAM (लं)

Function: Governs the instinctual mind and the foundation of being.

Purpose in Transformation: Purify fear and insecurity → awaken grounded awareness and trust in life.

🟠 2. Swadhisthana Chakra – Sacral Chakra

Location: Lower abdomen, below the navel

Element: Water

Quality: Emotion, creativity, desire, pleasure

Beej Mantra: VAM (वं)

Function: Regulates emotions, sexuality, and creative energy.

Purpose in Transformation: Transform attachment and emotional instability → awaken pure creative flow and joy.

🟡 3. Manipura Chakra – Solar Plexus Chakra

Location: Navel region

Element: Fire

Quality: Power, will, transformation, confidence

Beej Mantra: RAM (रं)

Function: Seat of digestion (physical and mental), willpower, and self-esteem.

Purpose in Transformation: Transform ego and anger → awaken disciplined self-mastery and inner strength.

💚 4. Anahata Chakra – Heart Chakra

Location: Center of the chest

Element: Air

Quality: Love, compassion, balance, harmony

Beej Mantra: YAM (यं)

Function: Bridge between lower (physical–emotional) and higher (mental–spiritual) chakras.

Purpose in Transformation: Transform attachment and conditional love → awaken unconditional love and equanimity.

🔵 5. Vishuddha Chakra – Throat Chakra

Location: Throat

Element: Ether (Space)

Quality: Expression, purification, truth

Beej Mantra: HAM (हं)

Function: Communication, creativity through sound, purification of thought and emotion.

Purpose in Transformation: Transform falsehood and self-suppression → awaken truthful expression and spiritual sound (Nada).

🟣 6. Ajna Chakra – Third Eye Chakra

Location: Between the eyebrows

Element: Light (Mind)

Quality: Intuition, insight, perception

Beej Mantra: OM or AUM (ॐ)

Function: Command center of consciousness — integrates intellect, intuition, and will.

Purpose in Transformation: Transform confusion and duality → awaken wisdom and clarity.

⚪ 7. Sahasrara Chakra – Crown Chakra

Location: Top of the head

Element: Beyond elements (Pure Consciousness)

Quality: Bliss, divine connection, enlightenment

Beej Mantra: Silence or sometimes OM (ॐ)

Function: Union with the Divine; receptivity to higher consciousness.

Purpose in Transformation: Transcend ego → realize unity with the Supreme Consciousness.

✨ How Beej Mantras Function

According to Swami Vidyanand’s teachings:

Each Beej mantra is a sound vibration corresponding to the energetic frequency of its chakra.

Chanting or internally vibrating these mantras aligns and purifies the chakric energy.

When combined with asana, pranayama, and meditation, the vibrations work on four levels:

Physical – toning the nervous system and glands

Pranic – balancing energy flow

Mental – calming thoughts and emotions

Spiritual – awakening higher consciousness

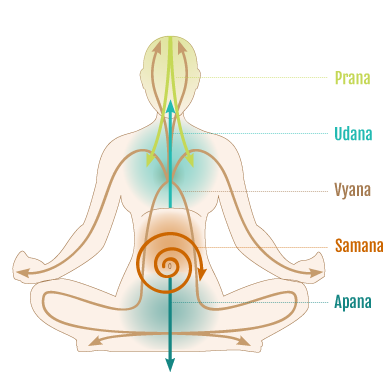

The Five Prāṇa Vāyus: Pathways of Vital Energ

In yogic philosophy, Prāṇa is the universal life force that animates all beings — the bridge between body, mind, and spirit.

Within the subtle body (sūkṣma śarīra), prāṇa flows through channels (nāḍīs) and organizes itself into five primary directional currents known as the Pañcha Prāṇa Vāyus — the five winds or vital airs.

Each vayu governs a distinct movement of energy and a set of physiological and psychological functions. Together, they sustain life and consciousness, much as the five elements sustain the physical world.

The Upaniṣads – The Birth of the Five Winds

The Praśna Upaniṣad (3.3–3.8) first names and describes the five vāyus:

“Prāṇa verily is the life of all beings… From this prāṇa are born the other prāṇas — Apāna, Samāna, Udāna, and Vyāna — each performing its own function in the body.”

Here, Prāṇa is seen as the chief life force, from which all other vāyus arise — each governing a different movement and aspect of life. This teaching roots the concept of the vāyus in the ancient realization that consciousness moves as energy within form.

The Bhagavad Gītā – The Yoga of Equilibrium

In Bhagavad Gītā 4.29, Krishna describes yogic control of breath:

“Others offer prāṇa into apāna, and apāna into prāṇa, restraining the courses of prāṇa and apāna, intent on prāṇāyāma.”

This verse symbolizes the union of upward and downward forces, leading to inner steadiness — the essence of Samāna Vāyu, which harmonizes all dual movements.

Patañjali’s Yoga Sūtras – Mastery of Prāṇa and Mind

While the Yoga Sūtras do not explicitly name all five vāyus, Patañjali describes their mastery through prāṇāyāma and saṃyama:

II.49–53 – “Prāṇāyāma is the cessation of the movement of inhalation and exhalation.”

→ The gati (movement) refers to the control of the vāyus. When they are balanced, the mind becomes still and luminous.III.40 – “Through mastery of Udāna, one becomes unaffected by water, mud, or thorns, and can leave the body at will.”

→ Points directly to Udāna Vāyu, the upward current that enables transcendence and resilience.III.41 – “Through mastery of Samāna comes the radiance of inner fire.”

→ Refers to Samāna Vāyu, governing digestion, assimilation, and the awakening of inner brilliance (tejas).

The Haṭha Yoga Pradīpikā

Haṭha Yoga Pradīpikā (2.2) states: “When prāṇa moves, mind moves; when prāṇa is still, mind is still.”

Control of vāyus through bandha, mudrā, and prāṇāyāma is essential to awakening kuṇḍalinī.

1. Prāṇa Vāyu

Direction of Movement: Inward and upward

Primary Region: Chest, lungs, and heart

Main Functions:

Governs inhalation and the intake of energy

Controls sensory perception and vitality

Nourishes enthusiasm and inspiration

Supports the functioning of lungs and heart

2. Apāna Vāyu

Direction of Movement: Downward and outward

Primary Region: Pelvic floor, lower abdomen, legs

Main Functions:

Governs excretion and reproductive processes

Grounds energy and promotes stability

Assists in elimination — physical, emotional, and energetic release

Anchors prāṇa in the body, giving steadiness and calm

3. Samāna Vāyu

Direction of Movement: Inward toward the center

Primary Region: Navel, solar plexus, digestive organs

Main Functions:

Governs digestion, assimilation, and metabolism

Balances Prāṇa (upward force) and Apāna (downward force)

Activates the digestive fire (jāṭharāgni)

Supports mental clarity and emotional equilibrium

4. Udāna Vāyu

Direction of Movement: Upward and ascending

Primary Region: Throat, head, and upper spine

Main Functions:

Governs speech, expression, and growth

Uplifts energy and consciousness

Supports memory, effort, and willpower

Assists the soul’s upward movement at death or deep meditation

5. Vyāna Vāyu

Direction of Movement: Expansive and circulating in all directions

Primary Region: Entire body and subtle energy field

Main Functions:

Governs circulation of blood, lymph, and prāṇa

Integrates the actions of all other vāyus

Coordinates movement and nerve impulses

Expands awareness, connecting the whole system in harmony

Example pranayama practices that allow you to exoereince each vayu:

1. Prāṇa Vāyu — Vital Inflow

Suggested Practice:

Sit comfortably (Sukha Āsana or Vajrāsana) with spine erect.

Take slow, deep inhalations expanding gradually from belly → ribs → chest (three-stage inhalation).

Exhale naturally or gently, releasing with ease (not forced).

Practice for 8–10 rounds.

After a few rounds, you may hold a short kumbhaka (retention) after inhalation — just comfortable, no strain.

Therapeutic Intent (Vidyananda alignment):

This kind of approach corresponds to nourishing the system, increasing prāṇic supply, and supporting the vitality of the lungs, heart, and upper torso. In Yoga Therapy, increasing prāṇa can help with fatigue, weakness, or low energy states.

How It Helps You Sense the Vāyu:

You might notice a subtle lifting in the chest, a feeling of inner expansion, or a warmth/delicate vibration around the heart region. This is the inward/ upward pull of Prāṇa Vāyu being reinforced and felt.

2. Apāna Vāyu — Grounding and Release

Suggested Practice:

Sit in a stable, grounded posture (e.g. Vajrāsana, Sukhasana).

Breathe gently, but extend the exhalation longer than the inhalation (for example, inhale count 4, exhale count 6 or 8).

At the end of the exhale, softly engage Mūla Bandha (root lock), holding it for a moment (if comfortable) before the next inhalation.

Practice 8–10 rounds, gradually extending exhalations as comfort permits.

Therapeutic Intent (Vidyananda alignment):

This technique helps release toxins (physical, subtle), anchors energy in the lower body, supports elimination, and brings stability. For conditions of “restlessness,” grounding the prāṇic flow is therapeutic.

How It Helps You Sense the Vāyu:

You may feel a downward pull of energy into the pelvic floor, legs, and earth. There may be a sense of release or letting go, a settling quality in the lower belly or groin.

3. Samāna Vāyu — Central Assimilation

Suggested Practice:

Sit erect, hands resting gently over the navel (or one hand there).

Use equal inhalation and exhalation, with an optional short kumbhaka (retention) after each exhale or inhale. For example, inhale 4, exhale 4, retain 2–3 counts (if comfortable).

You may combine this with gentle focus on the navel area (visualization or mindful awareness).

Practice 6–8 rounds.

Therapeutic Intent (Vidyananda alignment):

This balances the upward and downward flows, stimulates digestion (physical and energetic), and supports healthy integration of prāṇic rhythms. In Yoga Therapy, this kind of middle balancing is central to restoring homeostasis.

How It Helps You Sense the Vāyu:

You might feel warmth or pulsation around the navel/solar plexus. A subtle “churning” or central vibration can arise. You may sense that energies above and below are meeting in a neutral balance.

4. Udāna Vāyu — Ascending Expression

Suggested Practice:

Sit upright, slightly cooling and calm posture.

Practice Ujjāyī Prāṇāyāma (soft oceanic “s” sound in throat) with a gentle emphasis on the upper breath, letting the sound vibrate in the throat region.

Alternatively (or in combination), do Bhrāmarī (humming bee breath) with long, slow exhale, focusing vibration upward.

Repeat 6–8 rounds.

Therapeutic Intent (Vidyananda alignment):

This technique helps lift energy, supports clarity of speech, expression, and mental elevation. In the therapeutic sense, it can help with throat issues, stagnation of expression, or a desire to uplift one’s consciousness.

How It Helps You Sense the Vāyu:

You may feel vibration in the throat, base of skull, or crown. A sense of lightness or an upward current, as though the breath is carrying awareness toward the head or higher centers.

5. Vyāna Vāyu — Expansion and Integration

Suggested Practice:

Sit comfortably or lie down, allowing full expansion.

Practice Anuloma Viloma (Alternate Nostril Breathing) with equal inhalation and exhalation (e.g. 4:4).

Optionally include Kevala Kumbhaka (a pause, if experienced and comfortable) between cycles.

Practice 8–10 rounds, then rest and sense the flow throughout the body.

The Three Gunas

The guṇas — sattva (clarity), rajas (activity), and tamas (inertia) — are the three fundamental qualities of prakṛti (nature, matter, or the field of experience).

They are first introduced by Patanjali in the Sādhana Pāda (Book II) and discussed in greater philosophical depth in the Kaivalya Pāda (Book IV).

Navigating Life's Complex Journey:

The intricate journey of life can both confine and liberate us. To understand this duality, the ancient Indian philosophy of Samkhya, which means “that which sums up,” categorises reality into two main elements: the knower (purusha) and the known (Prakriti). Purusha, or the Self, is the conscious subject—constantly aware and knowledgeable. In contrast, Prakriti encompasses everything surrounding us in the objective universe, whether it is psychological or material; it is everything that can be perceived. The unmanifest aspect of Prakriti is a wellspring of infinite possibilities, characterized by three fundamental forces known as the gunas: sattva, rajas, and tamas, which interact in a state of balance.

This interplay gives rise to the manifestation of the universe itself. Thus, everything in this world, tangible and intangible, derives from the various expressions of the gunas. Gaining awareness of how the gunas function is an essential tool for spiritual growth. By learning to recognize the essence of each guna and utilizing that insight, you can move closer to identifying the Purusha within you.

A Closer Look at the Gunas

The term "guna" means “strand” or “fibre,” suggesting that, like the strands in a rope, the gunas intertwine to create the objective world. This theory provides a framework for understanding the composition of the universe and its manifestations as both mental and physical phenomena.

For those on a yoga path, being attuned to the gunas reveals whether we are making genuine progress in life (sattva), merely treading water (rajas), or veering off course (tamas). Each guna has unique properties.

Sattva is akin to a transparent window through which conscious awareness can shine, enhancing clarity in both the mind and nature. It isn’t enlightenment but reveals what is valid, embodying qualities like beauty, balance, and inspiration. Cultivating sattva involves making life choices that elevate awareness and cultivate unselfish joy, a primary aim in yoga practice.

Rajas represents dynamic change fueled by passion, desire, effort, and sometimes suffering. This energy can either uplift spiritual understanding (sattva) or more profound ignorance (tamas). While rajas can catalyze movement, it is often characterized by restlessness, agitation, and dissatisfaction—prompting change simply for the sake of change. For instance, while fresh tomatoes may embody sattva, a spicy tomato sauce represents rajas—enjoyable for a treat but perhaps not ideal for daily consumption. Rajas encourages sensory engagement but can also tether us to attachments and sensory desires.

Tamas obscures consciousness, fostering dullness and ignorance. It is heavy and tends toward inertia, often hindering action when needed. Tamasic food is unwholesome and lifeless, while tamasic entertainment tends to be mind-numbing and addictive. Tamas presents challenges like lethargy, procrastination, and excessive sleep. The interactions among the three gunas are continuous. We can observe hints of their relationships even within our language, like “innocent pleasure” (blending sattva and rajas) or “rabid addiction” (where rajas exacerbates tamas).

While the guns are fundamental and enduring, their interactions are fleeting, often making us mistakenly perceive them as permanent. This dynamic can obscure actual reality (sat) and bind us to what is ultimately unreal (asat).

An example of the experiencing the Gunas at play

Imagine Alex heading to work each day, influenced by the three gunas: sattva, rajas, and tamas.

Sattva Day: On a day when Alex feels exceptionally balanced and clear-headed, he wakes up early, practicessome mindfulness or yoga, and prepares for his workday calmly. At the office, he interacts positively with colleagues, approaches tasks enthusiastically, and focus on collaboration and creativity. Alex feels a deep sense of satisfaction from completing projects and contributing meaningfully to the team, embodying a mindset of clarity and purpose.

Rajas Day: Alex might wake up feeling agitated or competitive on another day. He may have an important meeting, and the pressure to perform kicks in. He rushes through the morning routine, skipping breakfast to get to the office faster. Alex feels a strong urge to outshine a colleague during the meeting, leading to a tense atmosphere. He works frantically on tasks, often distracted and overwhelmed by the desire to achieve more than others, reflecting the qualities of rajas, characterised by speed and intensity.

Tamas Day: Finally, there are days when Alex struggles with lethargy and distraction. Maybe he stayed up late the night before, and hit the snooze multiple times when the alarm goes off. Arriving at the office, Alex finds it hard to focus; he may feel sleepy and disengaged during meetings, not absorbing what’s being discussed. His mind drifts, and he may procrastinate on essential tasks, embodying the characteristics of tamas. This sluggishness can lead to feelings of frustration and lack of productivity.

Insights gained from these qualities extend beyond your practice and can transform various aspects of your daily life. Working with the gunas typically unfolds through four stages:

1. The influence of the gunas operates mainly outside your conscious awareness.

2. You start to perceive the gunas in your surroundings (the rajasic atmosphere at a busy store or the sattvic melodies of classical music) and learn to identify their distinct qualities.

3. You become aware of your tendencies related to sattva, rajas, and tamas.

4. Ultimately, you begin to shape your interactions with the gunas—fostering sattva, moderating rajasic impulses, and engaging tamas for foundational rest and stability.

The Gunas in Everyday Life The gunas concept is integral to the teachings of the revered Bhagavad Gita.

In chapters 14, 17, and 18, Krishna elaborately describes the gunas, emphasising their capacity to “bind the immutable embodied One.” He later states that everything in the universe, whether earthly or divine, is influenced by these prakriti-born gunas. Given their pervasive nature, how can we work with the gunas effectively? Krishna urges us to hone our self-observation and discernment skills. His consistent message is that, with dedication and practice, we can learn to recognise the workings of the gunas and engage with them meaningfully.

Krishna provides practical illustrations of the gunas across various scenarios. For instance, he notes that: - The food you consume may (17.8–10): - Be nutritious and uplifting (sattva). - Be overly seasoned, which leads to discomfort (rajas). - Be spoiled or unfit for consumption (tamas). - The gifts you offer may (17.20–22): - Be given selflessly and at appropriate times (sattva). - Be begrudged with an expectation of return (rajas). - Be offered casually or disrespectfully (tamas). - Your commitment to spirituality may (18.33–35): - Promote harmony in your mind and body (sattva). - Be rooted in the pursuit of external desires (rajas). - Be clouded by fears and lethargy (tamas). - Your sense of happiness might (18.37–39): - Emerge from inner clarity and grow over time (sattva). - Be fleeting, initially pleasurable, but ultimately harmful (rajas). - Stem from complacency and neglect (tamas). Considering these observations from the *Gita*, it’s crucial not to misinterpret their strict delineations. They are not meant to incite self-judgment but to serve as guidance—indicators of your current state and aspirations.

The Five Kleśas -The Roots of Suffering

In the Yoga Sūtras (Book II, Sādhana Pāda, sūtras 2.3–2.9), Patañjali describes the five kleśas, the inner obstacles or “afflictions” that cloud perception and cause human suffering. They are the mental and emotional roots of ignorance, desire, and fear, which keep us bound to the cycle of karma and prevent realization of our true nature.

Yoga Sūtra II.3:

Avidyā-asmitā-rāga-dveṣa-abhiniveśāḥ kleśāḥ“Ignorance, egoism, attachment, aversion, and clinging to life are the five afflictions.”

They are described further in Sūtras II.4–II.9, and their weakening is key to liberation (kaivalya).

1. Avidyā -Ignorance or Misperception

Sūtra: Yoga Sūtra II.5

Anitya-aśuci-duḥkha-anātmasu nitya-śuci-sukha-ātma-khyātir avidyā

“Avidyā is the mistake of taking the impermanent, impure, painful, and non-self to be permanent, pure, pleasurable, and the Self.”

Meaning

Avidyā is fundamental ignorance or spiritual confusion — mistaking the transient for the eternal, the material for the spiritual, the ego for the Self (ātman). It is the root of all the other kleśas.

Commentary

Vyāsa calls it the field (kṣetra) for all other kleśas to grow. It distorts perception, causing us to identify with body, mind, and possessions rather than the witnessing consciousness.

Example

Believing “I am my job” or “I am my body” — so that when either changes or fades, suffering arises.

2. Asmitā-Egoism or I-ness

Sūtra: Yoga Sūtra II.6

Dṛg-darśana-śaktyor ekātmatā iva asmitā

“Asmitā is the false identification of the seer with the instrument of seeing.”

Meaning

Asmitā is the false identification of pure consciousness (puruṣa) with the mind or intellect (buddhi). It’s the sense of “I am this.”

Commentary

Ego is necessary for functioning, but when over-identified, it obscures the true Self. In meditation, as awareness separates from mental activity, asmitā weakens.

Example

“I am the thinker of my thoughts” — rather than realizing thoughts arise within awareness.

3. Rāga - Attachment or Desire

Sūtra: Yoga Sūtra II.7

Sukha-anuśayī rāgaḥ

“Rāga is attachment which follows from pleasure.”

Meaning

Rāga is clinging to pleasurable experiences and wanting to repeat or possess them. It arises from memory of past enjoyment.

Commentary

The mind seeks pleasure as a way to avoid the discomfort of separation or emptiness. Rāga keeps one chasing outer fulfillment, reinforcing samsāra (the cycle of craving and dissatisfaction).

Example

Constantly craving approval, affection, or sensory pleasure — “I need that coffee / compliment / relationship to feel okay.”

4. Dveṣa -Aversion or Avoidance

Sūtra: Yoga Sūtra II.8

Duḥkha-anuśayī dveṣaḥ

“Dveṣa is aversion which follows from pain.”

Meaning

Dveṣa is the repulsion toward experiences that caused pain. Just as rāga clings to pleasure, dveṣa resists discomfort.

Commentary

Avoidance is another face of attachment — both are based in ignorance of our unchanging nature. Dveṣa reinforces fear and intolerance toward what challenges the ego’s preferences.

Example

Avoiding a person or situation that triggers discomfort — e.g., refusing to meditate because it brings up anxiety.

5. Abhiniveśa-Clinging to Life or Fear of Death

Sūtra: Yoga Sūtra II.9

Sva-rasa-vāhī viduṣo’pi tathārūḍho’bhiniveśaḥ

“Abhiniveśa is the strong desire for life, which flows on by its own potency, even in the wise.”

Meaning

Abhiniveśa is the deep, instinctive fear of death and attachment to existence. It’s a primal self-preservation drive rooted in ignorance of the eternal Self.

Commentary

Even the learned, says Patañjali, are subject to it — showing how deeply embedded this fear is in the psyche. It dissolves only with direct realisation that the true Self is beyond birth and death.

Example

Anxiety about aging, illness, or loss of identity — or the subtle fear that arises when facing silence or stillness in meditation.

Relationship Between Kleśas and Guṇas

The kleśas are the psychological roots of suffering, while the guṇas are the energetic qualities of nature that influence our inner state.

When tamas and rajas dominate, the kleśas thrive — ignorance, craving, and aversion increase.

As sattva rises through yoga practice, clarity dawns, avidyā (ignorance) fades, and the natural radiance of puruṣa is revealed.

-

The Evolution of Yoga: From Ancient practices to Modern times

This journey invites us to explore how and why ancient mystics chose yoga, and how it gained popularity across continents. - Yoga began over 5,000 years ago as a means to connect body, mind, and spirit in India and has since spread worldwide.

Yoga is so much more than just mastering impressive poses we're all saturated with on social media. The actual term "yoga" comes from the Sanskrit word "yuj," meaning "to join" or "to unite," symbolizing the connection between body, mind, and soul.It invites you to return to a state of perfect balance and self-discovery, allowing you to feel one with the world. From the sacred practices of ancient mystics in India to today's global wellness studios, the core goals of yoga remain consistent: finding inner peace, gaining strength, and bringing clarity to our often chaotic lives.

Through the centuries, various styles of yoga like Hatha, Raja, and Ashtanga evolved, each offering unique paths to growth and tranquility. - Today, yoga serves as a popular practice for individuals of all ages and backgrounds, promoting health, calmness, and strength.

The Origins of Yoga: Ancient Mystics and the Birth of an Art Yoga's intriguing roots trace back to Ancient India. In the early days of civilization, before formal religions emerged, yogis in the Indus-Saraswati River Valley (present-day India and Pakistan) engaged in meditation, movement, and breath, seeking a connection with the universe.

Shiva and the Saptarishis: The First Yogi and His Disciples In yogic lore, the journey begins with Shiva, regarded as the first yogi or Adiyogi. Legends tell of Shiva meditating by a serene Himalayan lake, sending forth a peaceful, intense energy that attracted the seven sages, known as the Saptarishis. Eventually, these sages requested Shiva's teachings, becoming the first students of this ancient art and spreading his wisdom across Asia. However, India remained the heart of yoga, where it would evolve and thrive.

The Vedas and Upanishads: Early Scriptures The earliest mentions of yoga are found in the Rig Veda, one of the oldest texts, dating back over 5,000 years. These scriptures included hymns and mantras used by Vedic priests and hinted at early yoga concepts. The Upanishads, comprising about 200 sacred texts, expanded on these ideas by describing self-realisation and meditation, marking a shift from rituals to a more introspective practice aimed at uniting the individual spirit with the universal.

Development Through the Ages: From Philosophies to Physical Practices From approximately 500 BCE to 800 CE, recognisable forms of yoga began to emerge. Key figures like Buddha and Mahavira introduced important philosophical dimensions, emphasising peace and self-control.

During this time, yogis articulated three principal paths to inner growth: 1. Jnana Yoga (the path of knowledge) 2. Bhakti Yoga (the path of devotion) 3. Karma Yoga (the path of action)

The Bhagavad Gita, written around this period, elaborated on these paths, showing how they can lead to inner peace through the teachings of Krishna to Arjuna, a warrior facing his own struggles. Fast forward to the 2nd century BCE, where we encounter Patanjali often referred to as the "father of yoga", and the Eightfold Path systematically organised and documented its principles, although he did not inevnet yoga.In his influential: Yoga Sutras where he outlined the Ashtanga, or eightfold path, guiding practitioners towards enlightenment:

1. **Yama** – Moral discipline

2. **Niyama** – Positive observances

3. **Asana** – Physical postures

4. **Pranayama** – Breath control

5. **Pratyahara** – Withdrawal of senses

6. **Dharana** – Focused concentration

7. **Dhyana** – Meditation

8. **Samadhi** – Enlightenment While physical postures dominate contemporary discussions of yoga, Patanjali emphasised the importance of self-discipline and mental control.

Yoga’s Evolution: The Hatha Era and the Spread to the West Between 800 CE and 1700 CE, yoga transformed dramatically during the post-classical era, giving rise to Hatha Yoga, which emphasised physical practices and breathwork designed to prepare the body for deeper meditation. This period was a turning point; practitioners began focusing on physical aspects, developing postures and techniques known today. Hatha Yoga: Embracing the Body’s Potential Hatha yoga taught practitioners to view the body as both a temple and a means to attain inner peace. Influential teachers like Gorakshanath and Swatmaram Suri emphasised physical health to achieve spiritual states, introducing practical techniques that made yoga more accessible and appealing across India.

Swami Vivekananda: The First Yoga Ambassador to the West In 1893, Swami Vivekananda made a significant impact by introducing yoga and Hindu philosophy to Western audiences at the World’s Parliament of Religions in Chicago, introducing yoga as a "science of the mind" and igniting curiosity among intellectuals and seekers.

Yoga’s Core Practices: Integrating Mind, Body, and Spirit At its core, yoga offers much more than just physical workouts. Here are essential practices that create a holistic experience: 1. **Asanas**: The physical poses that ground you and prepare the body for meditation. 2. **Pranayama**: Breath control techniques that invigorate the body and calm the mind. 3. **Meditation**: Focusing inward to cultivate mental clarity and a sense of peace. 4. **Mantras**: Repetitive sounds that help ground the mind and enhance meditative focus.

Tirumalai Krishnamacharya (18 November 1888 – 28 February 1989) was an Indian yoga teacher, Ayurvedic healer, and scholar, widely regarded as one of the most significant figures in modern yoga. Often referred to as the "Father of Modern Yoga," his extensive influence played a crucial role in the development of postural yoga. Like earlier pioneers such as Yogendra and Kuvalayananda, who were inspired by physical culture, Krishnamacharya contributed to the revival of hatha yoga.

The early 20th century marked the beginning of the modern yoga boom, characterized by an influx of yoga masters traveling to the West. Influential figures like Paramahansa Yogananda, who authored *Autobiography of a Yogi*, and B.K.S. Iyengar, the founder of Iyengar Yoga, highlighted the mental benefits of yoga, making it accessible to a diverse range of practitioners.

In 1947, Indra Devi opened a yoga studio in Hollywood, attracting celebrity clients and further popularizing yoga as both a spiritual and physical discipline. The counterculture movements of the 1960s and 70s saw a significant surge in yoga's popularity, transforming it into a staple of healthy lifestyles across the Western world.

Yoga in Today’s World: Diverse Practices and Global Influence Yoga has evolved significantly from its ancient roots. Today, various popular styles cater to diverse preferences:

Hatha Yoga: A gentle introduction to basic poses and slow movements.

Vinyasa Yoga: Flowing sequences connecting breath and movement.

Iyengar Yoga: Focused on alignment and often utilizing props.

Ashtanga Yoga: A challenging sequence promoting strength and endurance.

Hot Yoga: Practiced in heated rooms to increase flexibility and detoxify.

Yin Yoga: Yin yoga is a slow-paced style of yoga that involves holding poses for extended periods, typically three to five minutes, to target deep connective tissues and promote relaxation and flexibility.

How Social Media Has Changed Yoga In recent years: social media has transformed how yoga is perceived and practiced, making it more accessible but also sometimes placing undue emphasis on achieving perfect poses. Nonetheless, it has fostered a supportive global community that encourages individuals to explore yoga's deeper essence.

Women and Yoga: Reclaiming the Practice While early history often focused on male yogis, women have increasingly dominated contemporary yoga communities worldwide, creating inclusive spaces that celebrate diverse practices suitable for all bodies.

Why Yoga is Here to Stay Yoga's journey from ancient India to a global wellness phenomenon reflects resilience, adaptability, and timeless wisdom. Beyond physical benefits, its true power lies in fostering peace, clarity, and connection in our lives. Whether you're seeking calm in a busy world or exploring self-discovery, yoga provides a sanctuary that meets you where you are, transcending mere workouts to offer a pathway to wellness and unity. Yoga, at its essence, is a way of being.

-

All employees should be encouraged to attend a corporate wellness day retreat. However, the specific employees who attend may depend on the focus and goals of the retreat.

-

-